From Sea to Shining Sea: The Birth of Union Pacific

At 12:17 p.m. on May 10, 1869, telegraph cables around the country transmitted a single click, a single click that represented the greatest engineering feat of the 19th Century. The final spike was driven into the ground at Promontory Summit, Utah signaling the completion of the world’s first transcontinental railroad. The work of over six years and 20,000 men was finally over, creating a 1,774 mile long railroad that would both unite a nation and tear it apart. The creation of the railroad that changed the American way of life was taken up by two entrepreneurial companies, Union Pacific and Central Pacific, that had taken big risks to get big returns. The story of the founding of Union Pacific was one stained with corruption, greed, and exploitation. The company that built half of one of the greatest railroad in history and changed the American free market forever would not have been possible without the courage and determination of a few daring men and their clever yet unethical actions.

The story of the railroad begins not in 1863, but rather in 1848 with the discovery of gold in Western California. The discovery led to a mass migration of Americans who left the eastern United States and began the long and treacherous trek west to the “land of gold” hoping to strike it rich. There were only three paths available to the prospective gold miners. They could choose to travel by station coach across the wide American prairie and the treacherous western mountain ranges, a journey that often took over six months. They could also choose the long sea voyage, braving the rough waters around the southern tip of South America. The third choice was the shorter but equally dangerous route of crossing Panama by land, a region filled with disease and violence. Despite the difficulties in traveling, tens of thousands of gold-lusting men migrated to “the land of gold.” Many new miner settlements, populated by the hundred-thousands of Americans who had settled California by the end of 1849, including San Francisco and Sacramento, had sprung up and become bustling towns on the west coast. Despite their exponential expansion rate, the largest obstacle in allowing these towns to match the grandeur of the large bustling cities of the eastern United States was their seclusion from the rest of the country. It could take months for raw materials, manufactured goods, and people to travel between California and the rest of the United States.

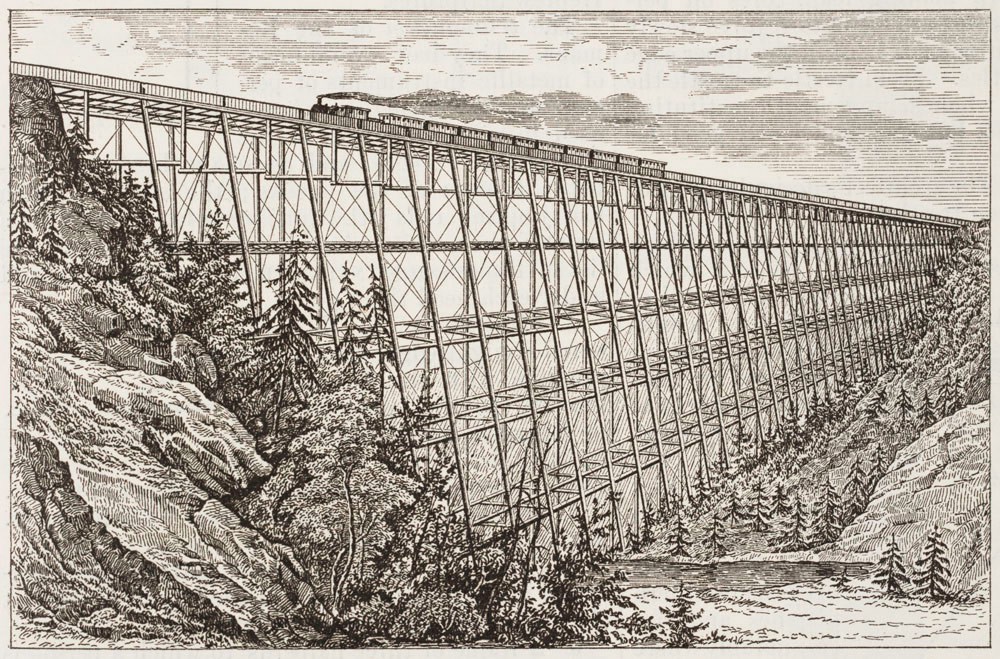

The people of the United States realized that if they were to utilize the vast natural resources of the West and protect these new settlements on the frontier, they would have to connect the East and the West. They looked to the emerging railroad industry, which had already laid over 15,000 miles of track connecting much of the Eastern United States, allowing Americans on the east coast to travel quickly and safely from city to city.

In 1853, Congress authorized government-sponsored explorations called the Pacific Railroad Surveys to find possible routes to the Pacific Ocean. Under the supervision of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, five potential routes were mapped and presented to Congress in twelve volumes. The northernmost route followed the 47th latitude from St. Paul, Minnesota to Seattle in the Washington Territory. The central route ran along the Platte River from Omaha, Nebraska to San Francisco, California. The route known as the Buffalo Trail ran through the New Mexico and Arizona territories to Southern California. Due to political tensions in Congress, no route was settled upon. Davis, a Mississippian, and the southern states wanted a southern route while the northern states backed a northern route. This standstill did not stop a few small bands of private surveyors from setting out west, beyond the Mississippi, to try to find their own path through the country that could serve as the path for the railroad.

One such surveyor was Grenville Dodge. Dodge was born on April 12, 1831 in Massachusetts. He was a railroad enthusiast, getting his first job at age 14 as a surveyor for Frederick Lander, another able surveyor. Impressed by Dodge’s ability and skill, Lander suggested Dodge attend Norwich University in Vermont to become an engineer. In 1848, when Dodge entered the University, he found it “filled with enthusiasm for expansion of railroads from the Atlantic to the Pacific.” Two months after completing his degree, he went to Illinois where he got a job at the Illinois Central railroad company. Dodge soon quit because he was much more interested in the Rock Island railroad company’s westward expansion than the Illinois Central’s southward expansion. In 1852, Dodge worked closely with Peter A. Dey of the Rock Island company to construct the Mississippi-Missouri railroad. Dey, one of the best railroad engineers in the country was very satisfied with Dodge. He once said: “Very soon I discovered that there was a good deal in him. I discovered a wonderful energy. If I told him to do anything he did [it] under any circumstances. That feature was particularly marked.” Dey, recognizing Dodge’s leadership, gave him his own stretch of land west of Iowa City, which he was responsible for surveying.

In 1853, Dodge led a party of fourteen men from Iowa City, hoping to reach the Missouri River before winter settled in. Dodge loved the wilderness he was exploring; he once wrote to his father: “Oh, that you could come out and overtake me on the prairies of Iowa, look at the country and see how we live. We shall make an examination of the great Platte as far into Nebraska as we think fit.” The open country of Iowa amazed the young engineer from New England. When Dodge arrived at Council Bluffs, it had a population of less than 2,500, but at first glance, Dodge thought to himself that this was the perfect site for the eastern terminus of the transcontinental railroad. After crossing the Missouri River on a flat boat, Dodge continued his expedition another 25 miles west of Omaha, a town with a population of 500, until he found the Elkhorn River at which point he turned back to Illinois.

In July 1855, Dodge met with his old mentor, Frederick Lander, who had just completed a survey of the Washington Territory. He confirmed Dodge’s belief that a railroad along the 42nd parallel (making Omaha its eastern terminus) was the most logical path for the transcontinental railroad. After their meeting, Lander departed for Washington to oppose Jefferson Davis’s plan to build a southern railroad. Lander argued that while a southern railroad would be shorter, a central route would be cheaper and easier to defend in times of war. It would also be able to unite conflicting public and private interests. It would run on flat ground near water by following the valley of the Platte River.

Dodge was funded by railroad enthusiasts Henry Farnam and Dr. Thomas C. Durant, who had interests in the Rock Island company, to survey the route Lander had suggested. In 1856, he made a survey up the Platte Valley and beyond the Rocky Mountains and reported to his financiers. Durant then set out west to locate investors willing to invest in the railroad, but investors were wary because of the Panic of 1857, one of the worst financial recessions in American history. In 1858, Durant invited Dodge to New York City to attend a meeting to propose to the board of directors of the Rock Island company their idea for the railroad. Dodge reports that by the time the meeting had closed, the only three people left in the room were Durant, Farnam, and him. Everyone had left calling the proposal impossible and a waste of their time. The three men left were still strong in hopes and were determined. Durant and Farnam decided to stay in New York to continue scouting investors while Dodge left for Council Bluffs to begin making a grade, which is the process for creating the path that a railroad follows.

On August 13, 1859, an Illinois politician, Abraham Lincoln, made a speech in Council Bluffs. It gathered quite a large crowd due to Lincoln’s popularity in the previous year’s Lincoln-Douglas debates. After the speech, W.H.M. Pusey, a close friend of Lincoln’s, introduced Dodge to Lincoln as knowing more about railroads than any “two men in the country.” This caught Lincoln’s attention and he sat down with Dodge to ask him questions about the transcontinental railroad, a subject he was very interested in as he hoped to use it as a campaign platform in the next year’s presidential elections. Dodge told Lincoln about his plan for a path along the Platte Valley. Lincoln was immediately interested in what Dodge told him. The next year, Lincoln was nominated to be the Republican nominee for President, a great boon to the entire railroad industry. Lincoln, however, had graver problems on his mind. Just a few weeks after his inauguration, on April 12, 1861, the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter and the Civil War had started. Dodge had to put the railroad aside and join the army. To him, holding the country together north and south was more important than linking it east and west. The railroad, however, never left his mind nor Lincoln’s.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, another railroad revolution was brewing. The Californians were even more anxious for a railroad than their fellow Americans on the East Coast. For the Californians, life was difficult because it was very difficult to transport people, equipment, and basic supplies from the rest of the country. Four brave entrepreneurs took up the task meant for giants: Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker, often collectively known as the Big Four. They created their own company called California Pacific and had big dreams to make fortunes making the transcontinental railroad. They recruited the talented Theodore Judah as their chief engineer. They would become the Union Pacific’s greatest rival in the race to complete the railroad.

Back on the East Coast, the Civil War was still raging and in 1862, the Pacific Railroad Act authorized the creation of the Union Pacific company, the third company to get a federal charter after the first and second Banks of the United States. The 163 men appointed in the act served as the board of commissioners and had their first meeting in Chicago to work out a provisional organization for the company. Among this board were prominent railroad men, bankers, and politicians including five commissioners chosen by the president. Due to their disbelief in the feasibility of such a project, when the meeting opened on September 2, 1862, only sixty-seven of the directors came. Even among those who did show up, the majority had serious doubts about the possibility of building such a railroad. At the meeting, the attending commissioners selected Major General Samuel R. Curtis to be the temporary chairman, Chicago Mayor William B. Ogden to be president, and editor of the American Railroad Journal, Henry V. Poor, to be the secretary. The commissioners’ biggest problem was the first-mortgage nature of the government bonds which made it nearly impossible for the company to sell its own private bonds. The appointed directors arranged to open stock-subscription books in thirty-four different cities and to advertise in numerous newspapers. Despite their efforts, in the first four months of the sales, only 45 shares were sold to eleven men.

The biggest buyer was Brigham Young, the leader of the Mormons. Young thought that a transcontinental railroad would be necessary for his people, as it would connect Salt Lake City to the rest of the country. Due to this personal interest, Young bought five shares and was the only shareholder to pay in full. Durant, the Wall Street speculator who apparently put up the money for some of the other purchasers, bought twenty shares at ten percent down for himself and made the rounds of his friends, looking for them to subscribe. George Francis Train, an erratic promoter who had partnered with Durant to earn a fortune by smuggling contraband cotton from the Confederacy, took twenty Meanwhile, Dodge shares.

was still fighting in the Civil War and had received the rank of colonel in 1861. During the Battle of Pea Ridge in northwestern Arkansas, Dodge was badly injured, and during his recovery in a St. Louis hospital, men from the Union Pacific company urged him to quit the army and join the company. Dodge refused however, saying, “I have enlisted for the period of the war.” Over the next few months, Dodge received several offers trying to get him to quit the army and join the company. Dodge refused every time. At one point, despite his wife’s pleas, he turned down an offer from the Union Pacific to be the Chief Engineer and earn a salary of $5,000 a year. He wrote to his wife, “My heart is in the war; every day tells me that I am right, and you will see it in the future.” Even in the war, railroading never left his heart. Dodge was put to work designing railroads to move Union troops and supplies in the South. Dodge’s skill with railroading impressed his seniors. Ulysses S. Grant wrote of Dodge in his memoir:

Besides being a most capable soldier, he was an experienced railroad builder. He had no tools to work with except those of the pioneer — axes, picks and spades…General Dodge had the work finished in forty days after receiving his order.

Part of the reason that Dodge was so emotionally invested in the war was because he believed in what he was fighting for and supported the freedom of the slaves. It was his belief that one of the easiest ways to defeat the South was to arm the slaves so that they might fight against their masters. Dodge once said, “There is nothing that so weakens the south as to take its negroes.” Not all of his fellow officers felt the same way and did not want African Americans bearing arms for the Union. In the spring of 1863, General Grant dispatched Dodge to Washington to report to President Lincoln. Dodge confessed, “I was somewhat alarmed, thinking possibly I was to be called to account [for promoting the arming of slaves].”

He was surprised when he got to Washington and Lincoln wanted to talk about railroads, despite the fact that Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were preparing to march into Pennsylvania. The President had been charged by the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 to fix the eastern terminus of the railroad. He recalled his previous discussions with Dodge in 1859 and wished to consult with him before making his final decision. Lincoln showed Dodge letters from towns all across the Missouri River filled with pleas to start the railroad in their town. Dodge wrote in his autobiography: “I found Mr. Lincoln well posted in all the controlling reasons covering such a selection and we went into the matter at length and discussed the arguments presented by the different competing localities.” Once again, Dodge reiterated his belief that the Platte Valley route was the obvious choice from both an engineering and commercial point of view. In a somewhat blunt manner, Dodge also told Lincoln that the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 has too many deficiencies in it, which he enumerated. One of the deficiencies that Dodge pointed out was the difficulty to raise capital to build the railroad. Lincoln agreed and said he would do what he could on the matter. Dodge and Lincoln did not necessarily see eye to eye on every issue however. Dodge said that it would very difficult for the private sector to build the railroad and that government should take up the task. Lincoln, on the other hand, said that while the government would provide support and aid, it “had all it could possibly handle in the conflict now going on.”

Elated by the president’s reaction, Dodge departed for New York where he met with Durant and told him of the discussion with Lincoln. Dodge and Durant had kept in touch during the period of the war; it was Dodge who provided Durant with information for the contraband cotton scandal. According to Dodge, Durant “took new courage” at the news of Lincoln’s response. Durant once again offered him a job and once again Dodge refused, saying:

Nothing but the utter defeat of the rebel armies will ever bring peace…I have buried some of my best friends in the South, and I intend to remain there until we can visit their graves under the peaceful protection of that flag that every loyal citizens loves to honor and every fights to save.”

This patriotic speech spoke volumes about Dodge’s patriotism and dedication.

By September 1863, two thousand shares were subscribed at $1,000 dollars each — the minimum ten percent that had to be put down for a $10,000 share. With the down payments, there was a total of $2 million to build the railroad that would cost anywhere from $100 million to $200 million or more. Most American Capitalists found the investment too risky and were unsure of whether such a railroad could be built. Also, because of the war, there were far more, less risky, short term investments to be made.

With the 10 percent in hand, the Union Pacific called for a meeting for the stockholders. During the meeting, on October 29, 1863, the original commissioners were discharged and a formal board of directors was elected. The next day, General John A. Dix, the dignified former president of the Mississippi and Missouri railroad company, was elected president of Union Pacific. This title was just honorary, however, as the true leader of the corporation was Durant, who was made vice-president.

Durant had the reports of the earlier surveys by Dey and his then assistant, Dodge. Two months earlier, Durant had sent Dey on another expedition paid for entirely from his own pocket. Durant contacted Dey by telegraph sending him the message: “Want preliminary surveys at once to make location of starting point. Delay is ruinous. Everything depends on you.” On November 17, Durant got Lincoln to sign an executive order defining the eastern terminus as “so much of the western boundary of the State of Iowa as lies between the north and south boundaries of…the city of Omaha.”

Durant was eager to start working as Central Pacific had already had their opening ceremony 11 months earlier and had already begun building. Durant decided that Union Pacific must have a ceremony of its own in Omaha, even if only to get publicity. He ordered Dey to rush preparations and be ready by December 1. Dey did so and the ceremony was very grand indeed.

The citizens of Omaha flocked to the Ferry to where the ceremony was taking place. The governor of the Nebraska territory was given the honor of breaking the first shovel of dirt. Train gave an eloquent speech which inspired all that heard the excellent oratory. He started off with the line, “America possesses the biggest head and the finest quantity of brain in the phrenology of nations.” He went on to read congratulations from Lincoln and other dignitaries such as Secretary of State William Seward who wrote: “When this shall have been done disunion will be rendered forever after impossible. There will be no fulcrum for the lever of treason to rest upon.” The groundbreaking had brought speculators flocking to Omaha. Train himself bought 500 acres, some costing as much as $175 per acre. Dodge’s brother Nathan wrote to him exaggerating that, “every man, woman and child who owned enough ground to bury themselves upon was a millionaire, prospectively.” After the ceremony, Train wired Durant the message, “Five o’clock the child is born.” Durant was not entirely impressed for he had other plans in mind.

Durant was in the business to make money, not to build a railroad. During the ceremony, Durant was busy in the towns of Florence, which was just north of Omaha, and Bellevue, which was just south of Omaha. Durant had bought land both north and south of Omaha and planned to play the three cities against each other. In January of 1864, Durant ordered Dey to survey another from the town of De Soto, more than twenty miles North of Omaha. Instead of planning to begin building the line, Durant was just bombarding Dey with more possibilities. Dey was furious. He wrote to Dodge saying, “If the geography was a little larger, I think he [Durant] would order a survey round by the moon and a few of the fixed stars, to see if he could not get some depot grounds.” Enraged, Dodge wrote to Durant: “Let me advise you to drop the De Soto idea. It is one of the worst. Logic, Nature and President Lincoln dictated that the route run from Omaha to the Platte River and then west along the Platte Valley.” Still Durant persisted in his schemes. He was negotiated with businessmen of Omaha, Florence, Bellevue, and De Soto all at the same time, demanding that they give the railroad land for depots, rail, water storage, and more.

On January 1, 1864, President Dix signed a document formally appointing Dey as the chief engineer of the railroad and Colonel Silas Seymour as the consulting engineer. Seymour was a lazy and eccentric man who was given the nickname “interfering engineer.” He was chosen for the job, however, because his brother was governor of New York and the likely democratic candidate for President. Durant believed that it would be wise to have friends in both parties. Dey, eager to begin his surveys, sent two fine engineers, Samuel B Reed and James A. Evans, to run a line from the Black Hills to Salt Lake. They needed to start immediately if they were to finish by the autumn of 1884. Durant, however, refused to approve their expenditures. On April 4, 1864, Dey wrote to Dodge:

Durant is vacillating and changeable and to my mind utterly unfit to head such an enterprise…It is like dancing with a whirlwind to have anything to do with him. Today matters run smoothly and tomorrow they don’t…I could build the work for less money and more rapidly than can be done the way they propose to do it.

The majority of conservative capitalists refused to risk their fortunes and reputations on the railroad. They regarded its stocks and bonds as a reckless gamble for high stakes at long odds. George Francis Train realized the railroad would require an enormous amount of capital and it would be years before the railroad would return any dividends at all. They would have to find a way to raise money and provide short-term profits. Train decided that he would create a construction company that could make money through government loans and sales of land grants and stocks and bonds. A separate construction company would also limit the liability of the investors to the stock that they had. Most importantly, as stockholders in both the construction company and the railroad company, the investors could make a contract with themselves. Train thought it was a genius plan and once said, “An idea occurred to me that cleared the sky.” He mentioned his idea to Durant who gave him $50,000 to put it into action.

In March 1864, Train and Durant bought a failing, obscure Pennsylvania corporation called Pennsylvania Fiscal Agency that had been chartered five years earlier to do nearly anything it wanted. The company was not even organized until May 1863, and even then, it had no business until Durant and Train were made the directors. In May, the board of directors was expanded to bring in more men from Union Pacific. Train renamed the company Crédit Mobilier and made it a construction company. They were able to sell lots of stock in the company. Ben Holladay, the “Stagecoach King”, and founder of the Holladay stagecoach line, bought $100,000 as did many others. Train himself bought $150,000 and Durant bought more than double that. Train later claimed that it was “the first so-called ‘trust’ organized in this country.”

Crédit Mobilier made a fortune nearly instantaneously. The process worked by the Union Pacific awarding construction contracts to dummy individuals who in turn would then assign them to Crédit Mobilier. Union Pacific would then pay Crédit Mobilier by check, with which Crédit Mobilier would buy Union Pacific stocks and bonds at par. It would then sell them in the open market for whatever it could fetch. The construction contracts made huge profits for Crédit Mobilier, which was owned by the principal stockholders of Union Pacific. Simply put, it did not matter if the railroad ever got up and running because Crédit Mobilier would make a fortune just from building it. Historian Thomas Cochran says:

The procedure…often resulted badly for the original small investors who had bought the railroad bonds at or near par. But for the insiders, it meant excessive profits. In addition, it necessarily tended to vest control of the railroad in the hands of the chief stockholders of the construction company.

In short, Crédit Mobilier became the greatest American financial scandal of the 19th century.

Almost everyone in Congress knew that the 1862 act would have to be modified. In May 1864, a new bill was presented to congress. Despite overwhelming support, a few congressmen were against the bill. Representative E.B. Washburne of Illinois called the revised bill “the most monstrous and flabbergasted attempt to overreach the government and the people that could be found in all the legislative annals of the country.” He argued that “ the Wall Street stock jobbers are using this great engine for their own private means.” Washburne was right about his last accusation. Both Durant of Union Pacific and Huntington of Central Pacific were in Washington handing out money and stocks to make sure the bill was passed. Joseph P. Stewart, a lobbyist hired by Durant, distributed $250,000 in Union Pacific bonds including $20,000 given to Charles T. Sherman, the older brother of General William Sherman, for “professional services” and $20,000 given to Clark Bell for drawing up the bill. Despite Washburne’s protests, the bill was passed by both houses, and on July 2nd, it was signed by President Lincoln, becoming the Pacific Railroad Act of 1864. The act allowed the directors of Union Pacific and Central Pacific to issue their own first-mortgage bonds in an equal amount to the government bonds, thus making the government bonds second mortgage. The government bonds would be handed over by Washington upon the completion of 20 miles of track instead of the original 40. Also, in Mountainous regions, the companies could now collect two-thirds of their subsidy on a 20 mile section once the track was graded. Also the companies were granted rights to coal, iron, and other minerals on their land grants, which were doubled to provide ten alternate sections on each side of every mile. This gave the companies nearly 12,800 acres per mile of track. Also, to attract investors, the par value of Union Pacific stock was reduced from $1,000 to $100 and the limit on the amount held by any one person was removed. The act also allowed Central Pacific to build up to 150 miles east of the Californian border while Union Pacific could build no further than 300 miles west of Salt Lake City. No exact meeting point was yet designated, however.

Meanwhile, Dodge was serving under General William Sherman’s Sixteenth Army Corps. Just before Sherman’s capture of Atlanta on September 1, 1864, Dodge was shot in the head. He spent nearly the entire month in the hospital but was motivated to return to the army as soon as he recovered. In the hospital, however, he got a letter from Durant asking him to travel to New York as soon as possible to meet with the Union Pacific officials. So, in October, Dodge traveled to New York. When he got there, Durant once again offered to make him chief engineer of the Union Pacific and Dodge once again declined. He then departed on a boat down to Grant’s headquarters in City Point, Virginia. Grant offered him command of one of his divisions but Dodge said that he would prefer to serve in the West. Although Grant felt that Dodge was not up for serving with Sherman again, he humored him and suggested that he call on President Lincoln.

Lincoln sent Dodge much farther west than he had expected. Dodge was sent to St. Louis, where he became commander for the Department of the Missouri. Lincoln wanted him there because of the problems confronting the government from the Indian situation of the Great Plains and to protect the Union Pacific when it began building. Dodge’s reputation in the war could not have been better, especially for his skill in working with the railroads. The friendships he had earned were strong. Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan trusted him and he trusted them. Union General O.O. Howard observed that “Dodge could talk to Sherman as no other officer dared to do.”

By that December, Dey had graded and spent $100,000 on twenty-three miles of track west of Omaha. Dey nearly exploded with anger when Seymour suggested that they abandon the path. Seymour and Durant both favored a route up Mud Creek, an oxbow shaped detour that would add an extra nine miles. The detour would bring in an extra $144,000 in government and company bonds, 115,200 acres of federal land grants, and more profits for Crédit Mobilier. Tensions between Dey and Durant only heightened when Durant’s front man, Iowa politician Herbert Hoxie, offered a contract that said he would build the first 247 miles for $50,000 to $60,000 per mile. Dey’s plan, however, stated that the cost was only $30,000 dollars per mile. The contract was signed and immediately turned over to Crédit Mobilier. Durant ordered Dey to resubmit his proposal and make it $60,000 per mile. Dey thought about it for over many weeks and finally wrote to Durant that he believed that amount “would so cripple the road that it would be impossible to ever build [it].” After giving it much thought, on December 7, Dey wrote to Union Pacific President Dix to tender his resignation. He wrote: “My reasons are, simply, that I do not approve of the contract made with Mr. Hoxie…and I do not care to have my name so connected with the railroad that I shall appear to endorse this contract.” He wanted no part in the corrupt dealings and reluctantly “resigned the best position in [his] profession this country had ever offered to any man.” By the time Dey had left Union Pacific, the company had only graded just over 20 miles and had not laid a single tie, let alone any rails.

On December 6, 1864, the newly re-elected President Lincoln delivered his Annual Message to Congress. The war was the main topic but he gave a paragraph to the transcontinental railroad, calling it “this great enterprise”. He said:

[It] has been entered upon a vigor that gives assurance of success, notwithstanding the embarrassments arising from the prevailing high prices of materials and labor. The route of the main line of the road has been definitely located for one hundred miles westward from the initial point at Omaha City, Nebraska, and a preliminary location of the Pacific Railroad of California has been made from Sacramento, eastward, to the great bend of the Truckee River, in Nevada.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, Central Pacific was also hard at work. Although the Railroad Bill of 1864 had promised immense benefits, the company could not begin receiving its benefits until they completed 50 miles of track. By the end of 1864, the company was nearly broke and Central Pacific stock was selling at 19 cents on the dollar. Crocker, one of the Big Four, admitted that he was suffering from insomnia and “would be willing to give up everything I have in the world , in order to cancel my debts.” The company was already finished with 36 miles of track, only 14 miles away from being able to tap into the reservoir of government bonds that would have been able to fund the company and pay off its debts. However, their greatest challenge was yet come; every mile that Central Pacific built brought them closer to the towering Sierra Nevadas.

On January 15, 1865, Dodge received a telegram from Lincoln ordering him to pay special attention to Missouri, a state badly divided between the North and the South. Dodge, however, felt that his duty was to curb the Indians, who would burn, loot, rape, and rob American settlements. On January 7, 1865, Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians rode into Julesburg, Colorado; they killed 15 soldiers along with many civilians and they burned down all of the buildings. Soon after this event, Dodge moved his headquarters from St. Louis to Fort Leavenworth on the Missouri River in Kansas. Dodge sent out an order to all district commanders on the Great Plains; he said:

Place every mounted man in your command on the South Platte route; repair telegraph lines, attack all bodies of hostile Indians large or small; stay with them and pound them until they move north of the Platte or south of the Arkansas [River]. I am coming with two regiments of cavalry to the Platte line and will open and protect it.

Dodge was carrying out his special injunction given to him by Grant, “to remove all trespassers [Indians] on land of the Union Pacific Railroad.” He toured the entire region and made sure every single soldier was in the saddle hunting down Indians. The general manager of the Overland Telegraph notified Washington that communication had been restored from the Mi¬ssissippi to California. Grant wired him a query, “Where is Dodge?” The General Manager replied, “Nobody knows where he is but everybody knows where he has been.” Later that year, General Sherman had been made the commanding officer of the Military Division of the Mississippi. Sherman wrote in his Memoirs

My thoughts and feelings at once reverted to the construction of the great Pacific Railway, which was then in progress.I put myself in communication with the parties engaged in the work, visiting them in person, and assured them that I would afford them all possible assistance and encouragement.”

Dodge’s campaigning was critical to the success of the Union Pacific. Durant and his fellow directors, however, were desperate for a new Chief Engineer upon the departure of Dey. They offered Dodge a salary of $10,000 a year and stock in Crédit Mobilier if he resigned from the army and joined the company. In his reply, Dodge pointed out that a railroad could not be built across the Plains until the Indians were subdued. General Sherman, understanding this connection, backed Dodge and communicated his belief to the Union Pacific directors. Not a single one of the directors dared to challenge William T. Sherman, They telegraphed Dodge that the position of chief engineer would be held open for him until he finished his Indian Campaign.

On January 20, 1865, Lincoln called Congressman Oakes Ames. Lincoln told him:

Ames, you take hold of this. If the subsidies provided are not enough to build the road, ask double, and you shall have it. The road must be built, and you are the man to do it. Take hold of it yourself. By building the Union Pacific, you will become the remembered man of your generation.

Ames was glad to have Lincoln appeal to him and began to put his money and political clout into the enterprise. Together with his brother Oliver, he bought $1 million of Crédit Mobilier stock and loaned Union Pacific $600,000.

Meanwhile, the fight over the oxbow route had cost Union Pacific almost $500,000 and even more in good will. The Chicago Tribune called the oxbow and “outrage” perpetrated by “a set of unprincipled swindlers” intent on “building the road at the largest possible expense to the Government and the least possible expense to themselves.” To add to the problems even more, Engineer Samuel Reed reported that his surveys were:

Extremely difficult and dangerous [because of] hostility of the Indians everywhere. Until they are exterminated, or so far reduced in numbers as to make their power contemptible, no safety will be found in that vast district extending from Fort Kearney to the mountains, and beyond.

Furthermore, Durant faced a logistical nightmare. Getting building materials to Omaha required shipping them up the Missouri River from St. Joseph, Missouri, a path that involved navigating up 175 miles of winding river that was only navigable by steamboat for three or four months a year. The only wood that was available in the area was cottonwood, which was so wet that it would only last for two or three years. Along with this, laborers were so hard to get that Dodge even offered captive Indians for the grading.

In April 1865, as the Civil War came to an end, President Lincoln was shot and killed. While the railroad companies had just lost their most powerful friend, for the Union Pacific, it meant that thousands of young men from both the Union and Confederate armies were now unemployed. Also for both Central Pacific and Union Pacific, it meant that huge quantities of money were going to be suddenly released. With almost explosive force, the industrial, financial, and transportation systems of the North were let loose. On July 22, 1865 Harper’s Weekly ran an article called “Railroads in Peace-Time” that summed up the state of the railroad industry and predicted what was to be expected in the future. “From 1859 to 1864 the business of the roads had more than doubled,” it opened. It went on to state that in June of 1865:

Traffic returns show an average increase over last year of 30 to 40 percent — far in excess of those of the most active period of the war. This is an astounding fact, one for which not one among the best-informed railroad men or Wall Street financiers was prepared.

The articles goes on to state, “Our roads, at best, are only half built. The only cost, on the average, $40,000 a mile…”

Meanwhile, Dodge was returning from his Powder River campaign when he stumbled upon Lodgepole Creek in the Black Hills. Curious, he took 6 other men with him to explore up the creek, which eventually discharged itself into the South Platee River. When he got to the summit of the Cheyenne Pass, he headed south along the crest of the mountains to get a good view. What he saw amazed him. There were open meadows covered with grass and flowers with mountains on either side. Dodge wrote, “We followed this ridge out until I discovered it led down to the plains without a break…I believe we found the crossing of the Black Hills.” Soon afterwards, in April 1866, after completing his campaign, Dodge quit the army and took up his position as the chief engineer of the railroad.

Finally, after all of its problems in getting started, the Union Pacific railroad company was ready to embark on its journey to create 1,087 miles of track that would change the country. It finally had the capital, the leadership, and the right engineer to take on the task meant for giants. The company’s problems were in no way over for they would face many hardships in the years to come. However, they had finally got all the elements needed to complete the task and the work could finally truly begin. Union Pacific and its Western mate Central Pacific were about to become the biggest businesses in America. The two companies were about to set forth the first step in ushering in the new era of reconstruction that would be needed to mend the wounds of a fragile, reunited country.

WORKS CITED

PRIMARY SOURCES

Dodge, Grenville M. *How We Built the Union Pacific Railway. *Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, 1966.

Grant, Ulysses S. *Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. *Vol. 2. New York: C.L. Webster & Co., 1903.

Houghton, Gillian. *The Transcontinental Railroad: A Primary Source History of America’s First Coast-to-Coast Railroad. *New York: The Rosen Publishing Company, 2003.

Sherman, William T. *Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman. *Vol. 2. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1990.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Ambrose, Stephen E. *Nothing Like It in the World: The Men who Built the Transcontinental Railroad. *New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Bain, David Haward. *Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad. *New York: Viking, 1999.

Brands, H.W. *The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream. *New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Cochran, Thomas C. Railroad Leaders 1845–1890: The Business Mind in Action.New York: Russell, 1965.

Gordon, Sarah H. *Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life. *Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996.

Klein, Maury. *Union Pacific: Birth of a Railroad. *Vol. 1. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1987.

McPherson, James M. *Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. *New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Perkins, J.R. Trails, Rails and War: The Life of General G.M. Dodge.Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill, 1929.

Starr, John W. *Lincoln and the Railroads. *New York: Arno Press, 1981, reprint of 1927 ed.

Stein, R. Conrad. The Transcontinental Railroad in American History.Springfield, NJ: Enslow Publishers, 1997.

Williams, John Hoyt. *A Great and Shining Road: The Epic Story of the Transcontinental Railroad. *New York: Times Books, 1988.

PERIODICALS

Abbot, John S.C. “Heroic deeds of heroic men. VIII.– A railroad adventure.” Harper’s Weekly, July 22, 1865.

Andrews, W.R. “Gold Mines of California.” Rechester Daily Advertiser, 1849.

Athearn, Robert. “General Sherman and the Western Railroads.” Pacific Historical Review 5 (February 1955).