DAOifying Uniswap Automated Market Maker Pools

Over the past two years, Uniswap has become one of the most popular decentralized exchanges on Ethereum. You can learn more about it here or by watching the Epicenter episode I did with Hayden.

However, the current Uniswap design was selected for simplicity rather than optimality. Now that the simple instantiation has proven itself in the market, works such as Balancer and Curve Finance signal a desire to iterate on this design in order to suit more specialized use cases.

In this post, I will propose two main changes to allow for the higher level of customizability that will enable Uniswap to adapt and become a more versatile tool in the DeFi ecosystem:

- Add more customizability to Uniswap curves by turning liquidity pools into DAOs who can use governance to improve the parameterization of the curve and fee models.

- Introduce the ability for multiple Uniswap DAOs for the same trading pair to compete to provide the best value to users.

Part 1: “Uniswap DAOs”

I propose that Uniswap liquidity pools ought to act more like DAOs, in which the liquidity share token holders are the DAO members. These liquidity share token holders can then use governance to parameterize and customize their “Uniswap instance” to best provide a service to users.

Now, what is the scope of governance that can be voted upon? I suggest there are two primary things that would benefit from customizability in Uniswap: The Automated Market Making Curve Function and the Fee Model.

AMM Curve

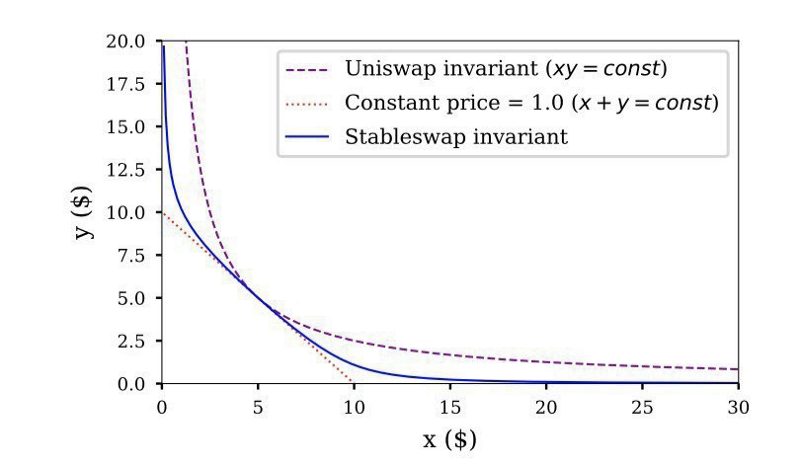

Uniswap currently uses a standard x*y=k curve for all pairs. However, there is a body of research being done these days that suggests that this may not be the ideal curve, especially for more specialized pairs like stablecoin to stablecoin, which projects like Curve Finance’s Stableswap and Maker’s Stablematic are optimizing for. Meanwhile other projects like FutureSwap are working on modifying the curve to enable more leverage-like trading experiences. There’s a lot of design space to explored in the construction of different curve algorithms, and what sorts of AMM curves best fit different specialized pairs/use cases, but that is out of scope for this article.

Fee Models

I will explain this one a bit more in depth, because it was this problem that originally got me interested in the direction after my Epicenter episode.

It is mathematically provable that without fees, it is always less profitable for someone to hold the liquidity pool shares than to just hold the underlying assets. The effect is magnified the more volatile the underlying assets are. Check out this article for a written explanation.

In Uniswap, this loss is offset by the fees, which are currently set to a fixed 0.3% * the trade size. However, this is likely too rigid for all cases, and may not sufficiently compensate liquidity providers, especially when dealing with highly volatile assets, if there is not already sufficient trading volume on the pair.

Allowing the multiplier to be a governance controlled variable rather than a fixed constant (0.3%) might be a good start. However, it might be even better to take into account more variables when calculating fee amounts, including the volatility itself!

As a market maker, there are three major things that you need to take into account: volume, spread (slippage), and volatility. The current fees method only takes into account one of them — volume, by making fees be a constant times the trade size (I believe Balancer does this). However, we could also take into account these other two variables as well.

The “spread” is pretty easy to get, it’s proportional to the slippage, and this is trivial to calculate for any given trade size, using the curve equation.

The “volatility”, however, is a bit more complex. It will involve taking into account the execution price of trades over a longer period of time, and thus storing and calculating the magnitude of price changes over a number of blocks. However, one of the expressed goals of Uniswap V2 is to become a better price oracle, which I imagine includes smoothing out volatility over singular trades, so I assume such price over time tracking system is already being built.

.@UniswapExchange doesn’t use price oracles because it IS a price oracle

— Hayden Adams 🦄 (@haydenzadams) November 25, 2019

Right now it’s only a useful (manipulation resistant) oracle for market makers on uniswap, but in V2 it will be useful for the rest of defi!

Uniswap v2 as a decentralized price oracle is gonna be🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥

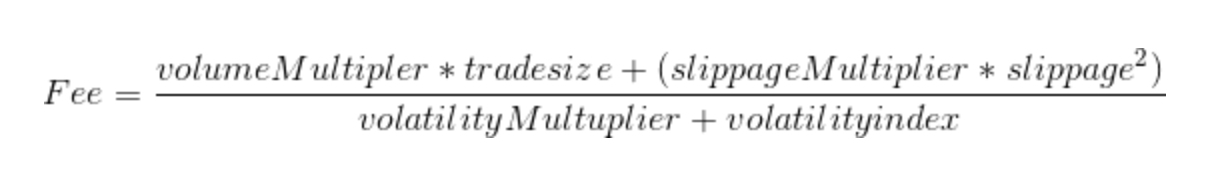

In the future a Uniswap fee model could go from being fixed as Fee = 0.003 * tradesize *to being an arbitrary function of these variables: tradesize, slippage, volatility index. It could be something as advanced as this (a completely made up example):

This may look daunting, but this complexity can be hidden from a user, as it generally already is in Uniswap interfaces. Meanwhile, it will provide better incentives for liquidity providers, thus improving the value delivered to users.

Furthermore, new fee types can be added as well. For example, Balancer proposes adding in an exit fee component (a fee for removing liquidity from a pool). Or another example is differentiating trading fees in different directions. If demand for a pair like ETH:DAI tends to be larger in one direction, it may be possible to reduce the fees in the other direction to better incentivize rebalancing.

Part 2: Uniswap Network

Great, now we have Uniswap DAOs with “on-chain governance” to be able to fine-tune curve algorithms and fee models. But what happens if you want to try out a new radical curve style or other deviation? Or you believe that the stakeholders are being too greedy, and that there is a better fee model that can attract more users, creating a positive sum for both users and liquidity providers. You’ve convinced a sufficient number of people, but not enough to win a governance vote. Well, there is a simple solution. Time to fork!

Just like the ability to fork holds chain governance systems in check, the ability to fork Uniswap pools holds its governance systems in check. What this means practically is that in this model, there needn’t be only one liquidity pool per trading pair. Rather, we can have multiple liquidity pools even for the same trading pair. I call this the Uniswap Network — multiple Uniswap DAOs competing with each other in the free market.

For example, two different ETH:DAI liquidity pools could co-exist and compete to find an optimal fee algorithm and curve structure to attract trading volume, while balancing the profit seeking motive of the liquidity providers. If one provides a better model or fee structure, more volume will switch to it, thus potentially earning more fees, and ultimately attracting more liquidity providers from the other pool.

Dividing Liquidity

One valid concern that pops up is that when we split liquidity for a single pair into multiple pools, the slippage of each pool increases, reducing the utility for users. There are two possible mitigations to this.

The first is by splitting trades across multiple liquidity pools. When making a trade, users will most likely not interact with a specific liquidity pool directly, but will more likely go through a Uniswap Network aggregator service (something like Kyber) that dispatches their order request to the optimal liquidity pool. When doing this, it can automatically split the order into multiple smaller orders, dispatching different pieces to different pools, which can often result in lower slippage than executing against a single curve. The aggregator service will optimize for minimizing slippage for the user.

The second mitigation makes use of that face that curves are now parameterizable. We can now create curves that offer less slippage, even at lower liquidities. For example, the Stableswap curve tries to reduce the convexity of the curve near the middle and increase it near the edges, thus providing less slippage for smaller trades.

This can be taken a step even further. In Part 1, we covered some of the variables that can be taken into account when designing fee models. However, we glossed over the design space of designing different curves. One avenue for exploration is taking into account the total liquidity in the pool in the curve structure. For example, a curve could be flatter (look more like the Stableswap curve) at low liquidities, and then increase the convexity as liquidity increases (move towards looking more like the uniswap curve).

Minimizing Exit Costs

What about bootstrapping new liquidity pools? You often need at least a minimum amount of liquidity to make a new liquidity pool viable. A minimum viable liquidity :D

However, you might have people who are interested in this new pool, but no one wants to be the first to join the new pool. Because while it’s below its minimum viable liquidity, it won’t be usable and thus not profitable enough for liquidity providers to switch.

Turns out this sounds extremely similar to a previous problem I once already solved! In the Cosmos SDK staking module, there is a maximum number of validators (125 currently) who are in the active set, and more in waiting. If the waiting validators can attract enough delegation, they can join the active set. As a delegator, I may want to delegate to one of those validators in waiting, but if I do and no one else does, then I won’t earn any staking rewards.

To solve this, I created a solution called commitment tokens. Essentially, I can delegate to a validator in the Top 125, but give a commitment to the validator in waiting. As soon as the validator in waiting receives enough commitments that they would be in the top 125, it triggers an auto-redelegation of everyone who gave them a commitment to redelegate to them, thus pushing them into the active set. You can watch my presentation on commitment tokens in this video starting at 15:23.

A similar mechanism can be created for the liquidity pools. When creating a new liquidity pool, I can propose a minimum viable liquidity as part of the curve specification, and allow people to issue commitments that will automatically switch their liquidity over to the new pool once it receives enough commitments.

Conclusion

I hope this reimagining of a “Uniswap Network” as a network of DAOs controlling AMM parameters and competing to provide the best value to users was intriguing. In no way am I making an absolute statement that this is the optimal future direction for Uniswap-like systems (To be honest, I’m not even sure I’m fully convinced on automated market makers at all, but that’s a story for another time!), but rather want to bring this model up for discussion with the larger community. I’ve also cross-posted this on ethresear.ch here which is a good place to discuss!

Thanks to Hart Lambur, Tina Zhen, Felix Lutsch, Dev Ojha, and billy rennekamp for helping review :)